hese were some of the reasons we decided to shot down the startup Sentar that our3-man team founded 18 months ago. We had the ambition to solve a big societal issue and recently got enrolled in Danish Tech Challenge 2017. So why did we decide to shut down our early stage startup shortly after? Because a bunch of mistakes we made. One serious mistake we made was being too eager to validate the need for our product. Another critical mistake we made was letting our strategic decision making be influenced by sunk costs. We would like to share our experience with this second pitfall here to let other future, present and former founders learn from the mistakes we made.

What is Sunk Cost?

Why write a lengthy explanation when someone made an awesome video about it?

I don’t have time to watch no video: What is she saying?

Real short “sunk cost” is cost that has already been invested and cannot be recovered. This could be time, money, energy etc.

The Sunk Cost Fallacy, or The Curse of Sunk Cost as we call it, is when you value the past investment too high in your decision making. You argue that you should do y because you have already spent so much time doing x.

An everyday example is: “I went all the way to a mall, but they didn’t have what I was looking for. But now that I have used all this time and energy to get here, I might as well buy something.”

Sunk Cost in Sentar

Looking back at our journey, the Curse of Sunk Cost showed its ugly face already 8 months in. In hindsight we actually see our startup, from that point in time, as a ship headed in one pre-determined direction. A ship with an increasingly heavy load making it harder and harder to change that direction.

In November 2016 we should have changed direction, but we were blinded by Sunk Cost. It’s always easy to play Captain Hindsight and argue what should have been done. Obviously we don’t know if changing direction 12 months ago would have made us succesful today.

But here goes the story about that cold November month in 2016, where we had one of the biggest arguments of all time, and where the Curse of Sunk Cost ended up making our strategic decisions for us.

Let’s set the scene. Mads, engineer and co-founder, and his fellow engineering student were halfway through their master thesis. They had dedicated their entire thesis to Sentar and worked full time on the thesis, which meant working a lot on Sentar.

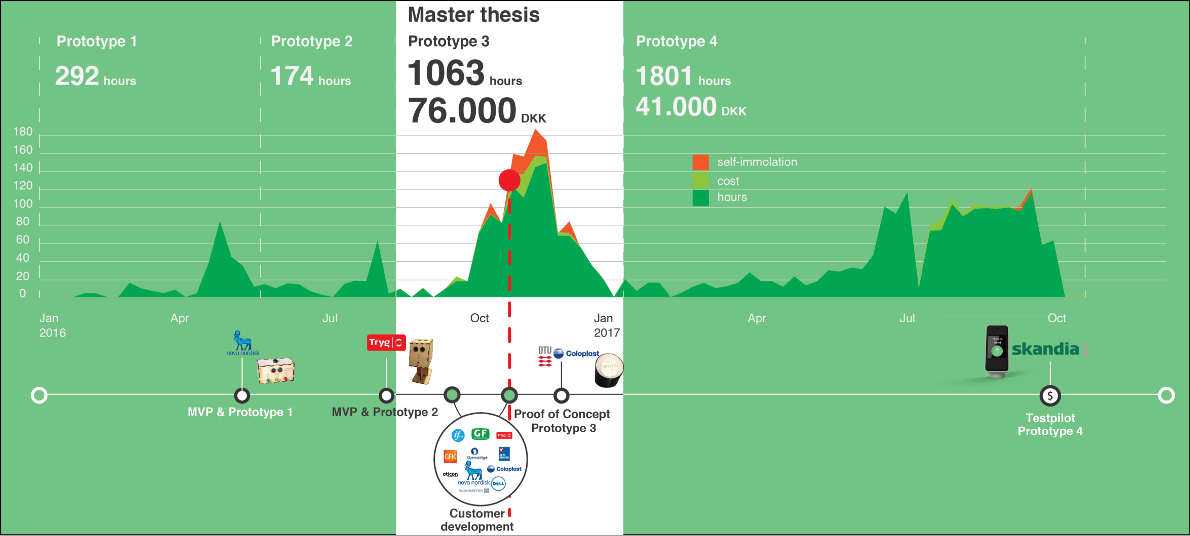

The primary goal of the thesis was to make a proof of concept with 50 prototypes tested for 2 months with real office workers. At the time of this story they had spent approximately 7,000 USD of Sentar’s money on materials and had started to build the first batch of prototypes.

Gantt-charts, detailed building schedules and test companies were lined up.

But Lasse — the business co-founder — was about to deliver some bad news. While the 2 engineers had rammed up their “production facilities”, Lasse had been interviewing customers in order to figure out whether or not there was a need for the product they were developing.

After talking to 10 HR managers it was clear — no one had an urgent need for our solution. We were not solving a valuable problem for them.

What you are seeing here is actually the exact amount of time spent on the various projects. Do not, or do, ask us why, but we have recorded all hours we have worked on Sentar — down to task level. You’ll hear more about this in the last article. (Self-immolation btw is the perceived sacrifices you make to reach deadlines)

Mads was leading the master thesis with 100 km/h putting in 70+ hours/week and now Lasse bursts into the office, and argues that what they are doing didn’t really matter. It didn’t make sense to our future customers. This was a truth Mads hard time coping with at that moment.

It ended up in a huge discussion about what to do, and these “facts” Lasse was bringing to the table really killed the teams’ motivation to reach the already tight deadlines.

And because we had already spent so much time and energy in this direction of making a big proof of concept, we decided to bury the “business validation” until we finished building and testing all the prototypes. Now we are finally at the mall, they didn’t have what we wanted, but now that we are here — let’s buy something, right?

But why were we cursed by Sunk Cost in Sentar? Here are 3 main reasons we are sure some of you will recognise in your own personal and professional lives.

Reason #1: The urgent need of having a clear goal and purpose

“If we are not developing prototypes, then what are we doing?”

This question often came up as the last argument in a discussion about what we should spend our time on. And while this is not a good argument, it reveals that our team needed a goal — a sense of purpose.

We found a document containing the Grand Plan 2017 for Sentar, which we made back in March 2017. Reading it now is almost embarrassing.

“Sentar has 2 major purposes in 2017.

1. Improve our proof of concept

2. Secure a solid proof of business”

Then we list 7 milestones where milestone 1–6 is about creating a new prototype, improve our UI and test 15 of these new prototypes.

The seventh milestone is then finally about business ?

“Milestone 7: 3 insurance companies have by December 2017 subscribed to our service, and thereby validated our business model.”

At this point the team is aware that it’s on shaky ground. But what is the easiest thing to make a plan about?

A) develop and test a new prototype, which will keep us occupied in 6 months

B) figure out if our customers need our product, which we don’t really know how to do

The need of having a clear plan overruled the important need of securing a proof of business.

This decision making behaviour looks stupid now — we know (enter Captain Hindsight).

But once again we have a model to explain our behaviour ? We didn’t know about this model while Sentar was alive, but OMG we wish we did.

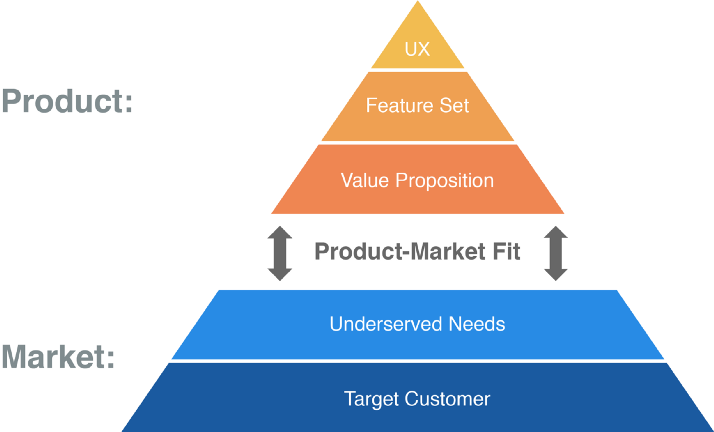

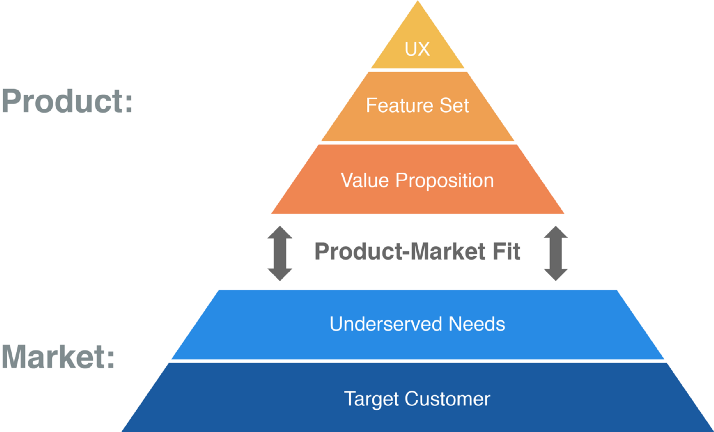

The Product Market Fit Pyramid: How some spend their time on the top, when they should dedicate 90% of their time to the bottom

We think that this model visualises all you need in an early stage startup. It shows you what the foundation of your startup is = a well defined group of customers with a set of underserved needs.

It also shows exactly how wrong our Grand Plan 2017 was. What we did was spend 90% of our time on the product. We discussed features over and over, tested the UX on users and spent weeks building arguments for our value proposition.

For us, and many others, it was very uncomfortable in the bottom. Working on the Product is going to the office, soldering, drinking coffee, brainstorming on white boards and eating lunch. Working on the Market is cold calling, being rejected over and over and having your customer meetings pushed and pushed.

And last but not least: facing the risk of customers telling you; “We don’t need your product.”

What should we have done?

Well, first of all we should have worked “smaller” and accepted short sprints with modest goals. Doing so would have helped us answer the 2 most important questions:

- Are we focusing on the most critical hypothesis/assumption/leap of faith question this week?

(Back in September 2016, after our small test with a large insurance company called Tryg, we actually knew, we could make office workers stand up more with the use of simple technology. From there on our most critical hypothesis was not if we could make this fragile proof of concept better, but instead if someone would pay for it.)- Are we investigating this critical subject/hypothesis/assumption in the most effective way possible?

Secondly, we know that we should have focused much more on the market than we did. But every time we tried to do so, it robbed us of direction, a sense of progress and the good vibes at the office. From here on out we will ask ourselves; Are we doing the right thing today or the nice thing?

From here on out we will ask ourselves; Are we doing the right thing or the nice thing today?

Reason #2: Mixing processes

One of the big reasons we built up a lot of Sunk Cost in Sentar was that we tied ourself up to at least 2 long processes which were not startup processes.

The first was this 5 month Master Thesis project you know of by now, the other a public grant for an 8 month innovation project.

We will use the Master Thesis project as the example of why it was a bad idea for us to mix “our startup process” and “the Master Thesis project”.

The purpose of the master thesis was to develop a product that would fit the market. The 2 guys would “take it from the top” and use Sentar’s previous research to throw everything at the wall to see what sticks.

It sounds awesome right? 1 co-founder can now dedicate almost all his time to the project as it becomes his main occupation. And even more awesome: he has convinced his thesis partner to spend all his time on Sentar.

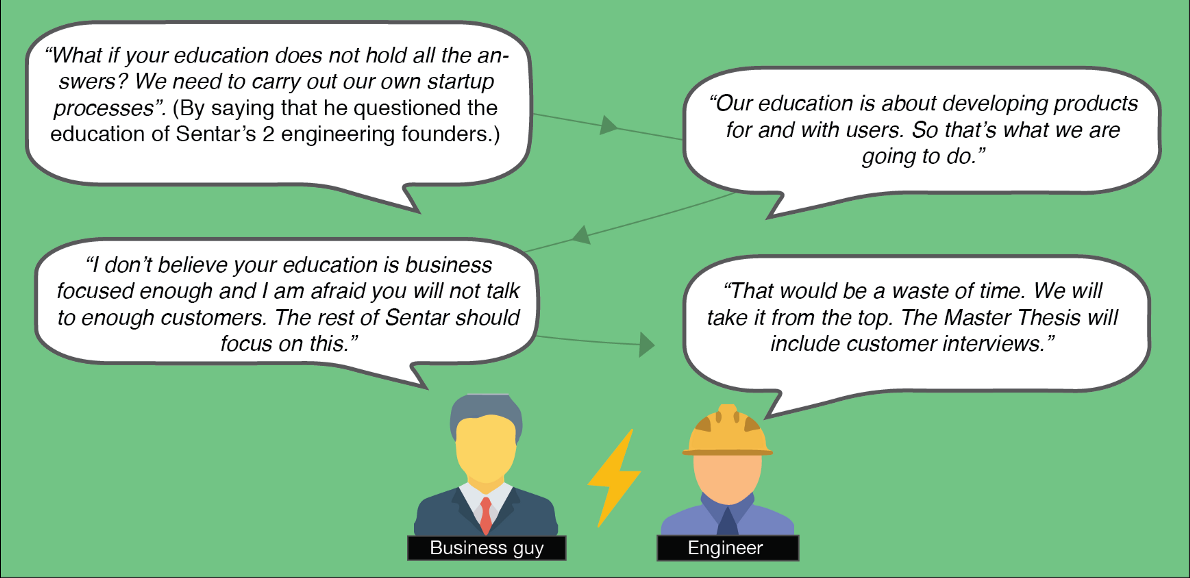

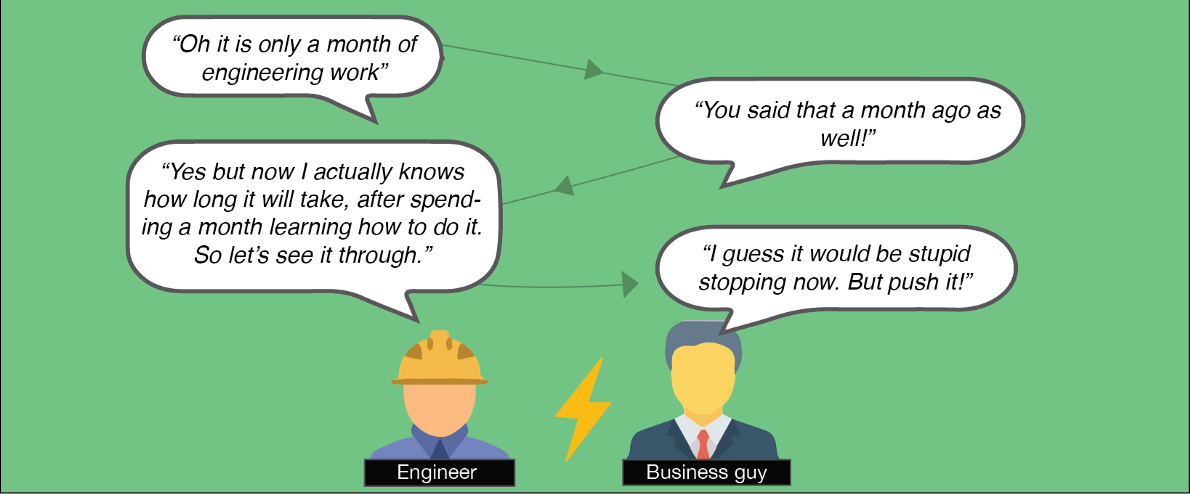

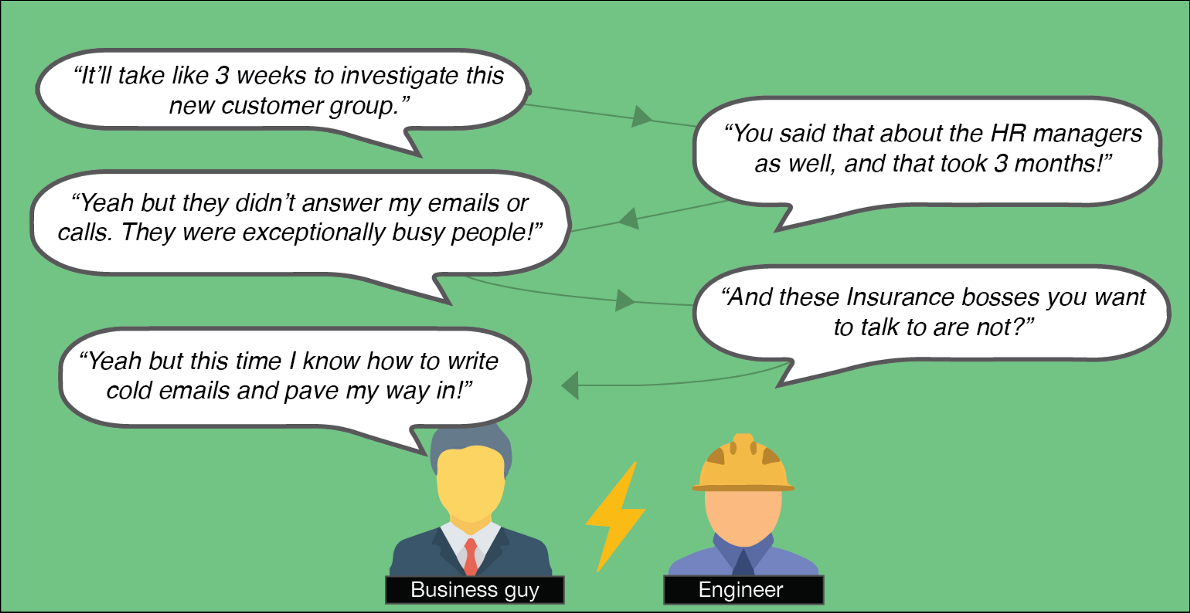

Heated discussion coming up: Are you saying we can’t make it?

Already before the process of the thesis started we got into a fight about the value of this thesis and the dangers of committing ourselves to it. The discussion went a bit like this:

It is safe to say that this is a nice version of the actual discussion. Worse things were said and eyes that could have killed filled the room.

The Curse of Sunk Cost just made it harder and harder to discuss this subject. Everyday the Master Thesis dedicated 10 hours to Sentar in “their” direction and each day the rest of Sentar dedicated only 2–3 hours next to their day job in “their” direction. This created an unbalanced power structure in Sentar, where one would have more power behind their argument if they had done more for Sentar (read: if they had built up more Sunk Cost for Sentar than others).

But this is what happens when you let an “outside” and lengthy process rule over your agile startup process.

Looking back we should have separated the Master Thesis completely from Sentar’s strategy. The project should have been about a technical part of Sentar or maybe about a user group. We should have been able to change focus completely in Sentar while the thesis could go on unaffected by Sentar’s change.

Instead the thesis ended up dictating the direction of Sentar from August-December 2016. And because the 2 engineering students worked more than what seemed possible, they built up an amount of Sunk Cost we just couldn’t ignore in our strategic decision making in 2017.

The other thing we would do differently in the future, is about having very different work loads amongst co-founders. This feeds the hard-working co-founder’s Sunk Cost monster. “I am sacrificing way more than the other guys. If I can’t even get to decide what we are doing, what is the point of this sacrifice?” Just think about how you would feel working 6 months on something and then someone comes along and says; “What you are doing is really a waste of time.” We promise you — you’ll find a way to justify the value of your work and how it forms the basis of the company going forward.

Reason #3: Crazy time optimism

Let’s just say very briefly: we would not have embarked on some of the very big projects, had we known how big they would become.

This reason seems a bit basic. But this is really one of the main reasons we built up too much Sunk Cost. Have you heard versions of these two discussions before?

or

We always seem to think that what we are going to do next will be linear, straight forward and easy, while what we have just done was hard, complex and took longer than expected because of bad reason x, y and z.

Most of our plans took twice the estimated time. And when you make a 2 month plan, and this suddenly takes 4 months, then you feel twice as stupid if you throw that in the trash, because the outcome wasn’t valuable after all.

Add to this the sacrifices you made, in order to keep your project at 4 and not 5 or 6 months. All the complaints from your girlfriend; “You’re spending all your time on Sentar.” Your family says; “Shouldn’t you spend your time on a solid career?” And you start thinking; “What could I be making elsewhere right now? What am I missing by dedicating all that I have to this project?”

These 3 things; Crazy Time Optimism, Your Perceived Sacrifices and The Curse of Sunk Costs makes heading in the wrong direction a downwards spiral that for us didn’t stop before November this year.

Do you want to read about the other two major mistakes we made?

This is the second article in a series of three about startup mistakes from the perspective of our own recent experience. The articles will be posted on this blog through December and January. Read our first article on trying too hard to validate the need for our product here or follow us on Medium!